I am currently a faculty member at a public university in Virginia. However, my family lives in Western New York State. Princeton, New Jersey, is just about halfway between my current home and my family. For that reason, I’ve made several trips through Princeton — in December 2024, January 2025, and — most recently — in September 2025.

Princeton is a microcosm of my historical interests. Princeton matters for American religious history; the Fundamentalist/Modernist controversy shook Princeton Theological Seminary in the first three decades of the twentieth century. Princeton also matters for the history and philosophy of physics; Albert Einstein, John von Neumann, and Kurt Gödel were faculty members at the Institute for Advanced Study. Princeton University’s faculty included John Wheeler from 1936 to 1976; in turn, Wheeler’s PhD students included Charles Misner, Richard Feynman, and Hugh Everett III. Here, I’ll describe how I’ve traced some of Einstein’s footsteps through Princeton.

When Einstein first arrived at Princeton in 1933, he visited a popular local establishment known as the Balt. Originally part of a chain known as the Baltimore Dairy Lunch, the Balt was deeply popular with Princeton students until closing in 1963. Apparently, the restaurant was so beloved that students held a memorial service for the restaurant that included a student who stood in as the restaurant’s corpse. According to Lou Cain, between 1921 and 1936, the Balt was known under its original name; the restaurant officially changed its name to the Balt in 1936. Hence, when Einstein visited in 1933, the restaurant would have had the original name. (I’ve seen the Balt mistakenly called an ice cream parlor. The Balt served ice cream, but also served lunch, as might be surmised from their name. A menu from 1939 can be seen here.)

Seminary student John Lampe stated that he saw Einstein order vanilla ice cream with chocolate sprinkles (source). Einstein was often seen walking on Nassau Street eating an ice cream cone. Apparently, that was eccentric behavior in the 1930s, though it wouldn’t be all that uncommon now. (I believe I read about this in Palle Yourgrau’s A World Without Time: The Forgotten Legacy of Gödel and Einstein.) The fact that doing so was uncommon may explain why ice cream entered Einstein lore. IQ — a goofy 90s-era romantic comedy starring Meg Ryan as Einstein’s fictional niece — depicts Einstein and his friends walking with ice cream cones.

The former location of the Balt has undergone several changes since the Balt’s closure in 1963. The Balt was located at 80-82-84 Nassau Street. That location is now three storefronts, one of which — 84 Nassau Street — is unoccupied, at least as of September 2025. The Nassau Diner, which occupies the middle third (82 Nassau Street), opened in 2023, but is intended as something like a spiritual successor to the Balt. Their menu contains an image of the Balt and — like the Balt — the restaurant includes marble tables. (From the photos displayed in the Updike Farmstead — see below — the tables in the Balt were black marble, while those in the Nassau Diner are white marble.) Unlike the Balt, the Nassau Diner is fairly expensive, though perhaps not unreasonable for a restaurant adjacent to Palmer Square. In September of 2025, Nora and I visited the Balt’s former location. The three storefronts still have the Balt’s distinctive tiling. The tiling helps to distinguish the Balt’s former location from the unrelated storefronts to either side.

On the left is a photo from the Balt’s closure in 1936. On the right is the now unoccupied storefront as of September 2025.

Left: A photo of me at the side of the unoccupied storefront. A portion of the Nassau Diner can be seen. Right: tiles in a doorway adjacent to the unoccupied storefront. I’m not completely sure, because I can’t find period photos that show this doorway in much detail, but I think the tiling was part of the original Balt. The doorway appears to lead to apartments above the three storefronts.

Above: Nora and I outside the Nassau Diner.

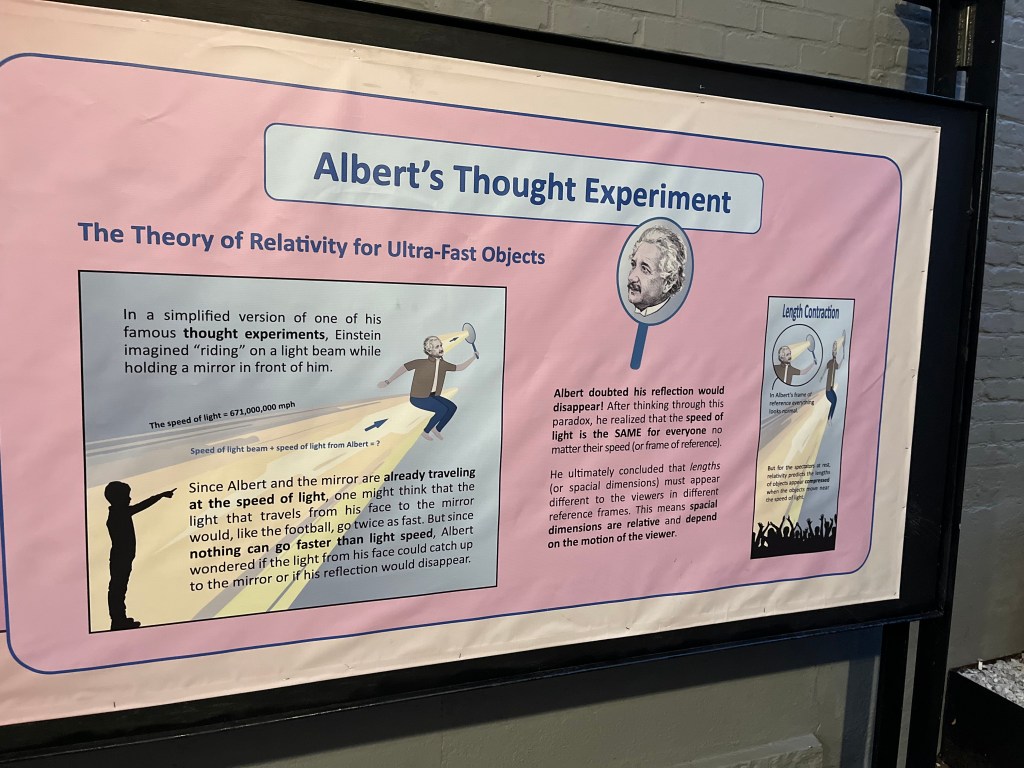

Located further down Nassau Street, Dohm Alley includes space for public exhibits. The current exhibit doubles as advertising for the planned Princeton Einstein Museum of Science. As an Einstein aficionado, I’ve been waiting several years for that project to come to fruition. The fact that it hasn’t happened yet makes me wonder whether the project is defunct.

Back in December 2024, Nora and I visited the Updike Farmstead, now a museum maintained by the Historical Society of Princeton. I didn’t realize the historical significance at the time, but the farm has a stool and a table from the Balt, as well as several photographs.

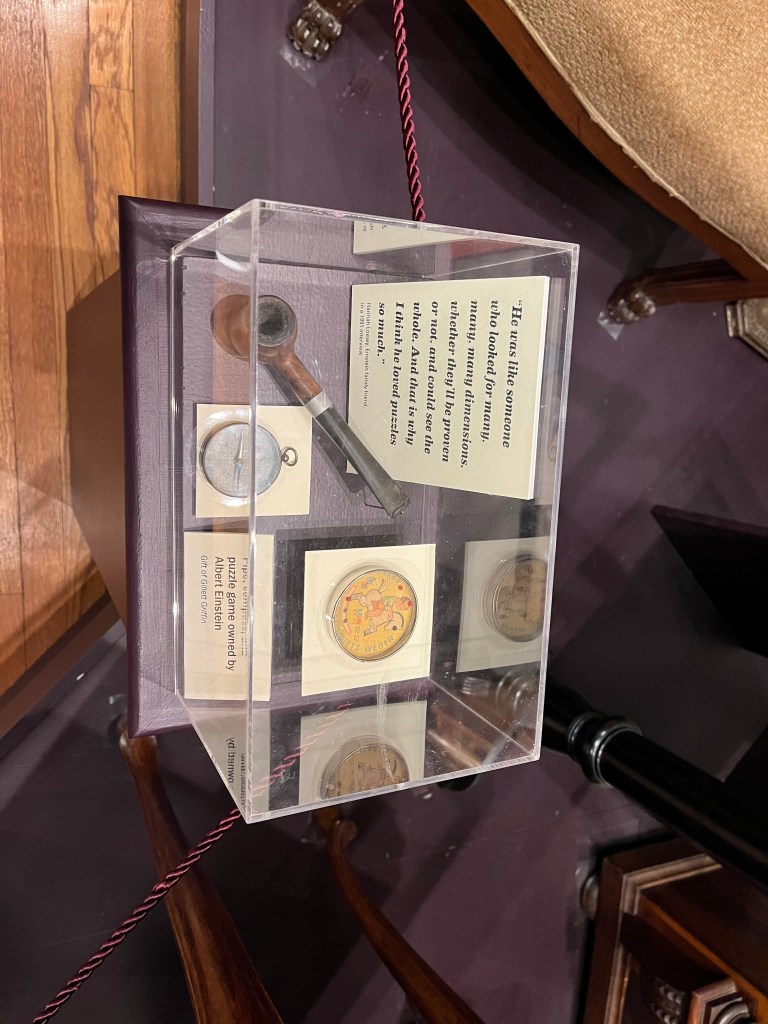

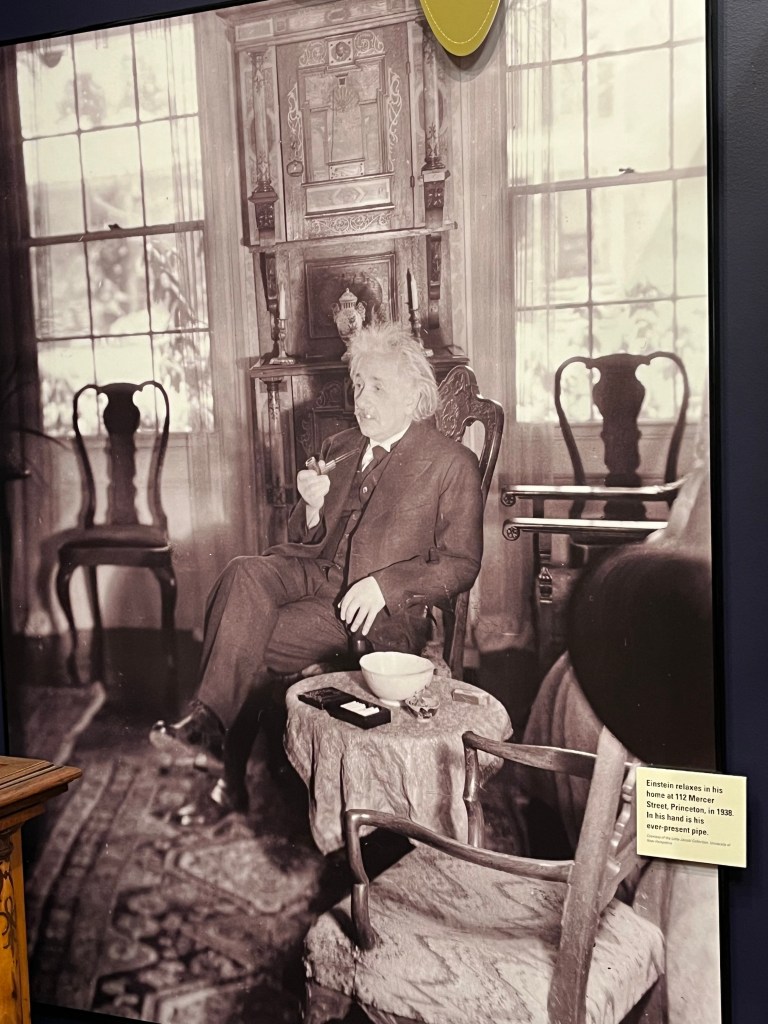

The Updike Farmstead Museum also has a small display about Einstein. The display includes Einstein’s furniture — which was smuggled out of Germany (see below) — and Einstein’s pipe, compass, and puzzle game. The pipe and compass have particular significance in Einstein lore. Much in the way that (for example) Ben Franklin is typically depicted with a kite, Einstein is typically depicted with a pipe. Einstein was photographed smoking several different pipes throughout his life (one of which is currently owned by the Smithsonian), but the one in the photo below appears similar to the pipe on the right.

In his ‘Autobiographical Notes’ (from Schilpp’s Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist), Einstein wrote that his father gifted him a compass when he was a child. The compass inspired Einstein’s love for physics. I’m not sure if the compass at the Updike Farmstead is the one his father gifted him, but surely it must have reminded him of his father. Again, there’s a scene in IQ that references the compass. (Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to locate a clip.)

We visited Einstein’s house on Mercer Street. The house is not a museum and is currently occupied. We didn’t want to disturb whoever occupies the house now, so I took a couple of quick photographs from across the street.

Left: A photograph of Einstein from around 1951. Middle and right: Two photos I took in December 2024.

There are some remembrances of Einstein’s home thanks to Wheeler. Wheeler taught his first graduate-level seminar in General Relativity at Princeton University in 1952. During a subsequent semester, on May 16, 1953, Wheeler and the eight to ten students in his GR course had tea at Einstein’s home on Mercer Street. A firsthand account — by Wheeler and three of his students — can be found here. Wheeler and his students sat at Einstein’s dining room table; tea was served by Einstein’s adopted daughter, Margot Einstein, and Einstein’s assistant, Helen Dukas. Wheeler’s course would later serve as the basis for the famous book Wheeler co-authored with Charles Misner and Kip Thorne. (In turn, Thorne is now known for his work on the film Interstellar, where several consequences of Einstein’s ideas are depicted in full Hollywood magic.) Almost exactly a year before his death, on April 14, 1954, Einstein gave a guest lecture in Wheeler’s GR seminar (source).

After Einstein’s death and cremation in 1955, Einstein’s furniture was moved out of his house on Mercer Street and stored at the Institute for Advanced Study. As of January 2025, the furniture was included as part of the exhibit on Einstein at the Updike Farmstead.

The house on Mercer Street features in another bit of Einstein lore. Like Einstein, Gödel came to the United States fleeing from the Nazis. Gödel was not Jewish — he was a fairly religious, albeit unorthodox, Christian — but the Nazis had labeled him a Jewish sympathizer. Gödel came to the United States the hardest way possible: the Trans-Siberian Railway across Asia and then a long journey across the Pacific. Apparently, Gödel took the long way to avoid the conflict in the Atlantic.

After making his way to the Institute for Advanced Study, Gödel became one of Einstein’s closest friends; though Gödel is better remembered for his contributions to logic — such as the incompleteness theorem — Gödel had an avid interest in physics. For Einstein’s 70th birthday, Gödel gifted him with a new solution to the Einstein Field Equations. In the new solution, there is a closed time-like curve through every spacetime point. The solution so massively butchers our intuitive notion of time that, for Gödel, we should give up on the notion of time altogether. Einstein is said to have been disturbed by the implication. (This is yet another bit of Einstein lore depicted in IQ. In the film, Gödel is played by Lou Jacobi. Jacobi’s Gödel is not only better fed than the historical Gödel — who starved himself to death — but also gives an absolutely bonkers argument against the reality of time during a tennis match.)

At any rate, Einstein and Gödel took long walks from their homes to the Institute for Advanced Study and back again. Yourgrau describes the pair as feeling alone in New Jersey — nostalgic for a Germany that no longer existed and in a country they came to relatively late in life. The long discussions the pair took on their journeys have a nearly mythical status; they were the impetus for two of Yourgrau’s books, an essay by Jim Holt, and are depicted in the film Oppenheimer. Since Einstein lived closer to the Institute than did Gödel, I think the path they followed must have begun with Einstein’s home on Mercer Street.

Left: A still from a scene in Oppenheimer filmed at the pond behind the Institute. In one of the film’s scenes, the titular figure interrupts Einstein and Gödel’s walk through the woods near the Institute. Right: A photograph I took at the pond in December 2024.

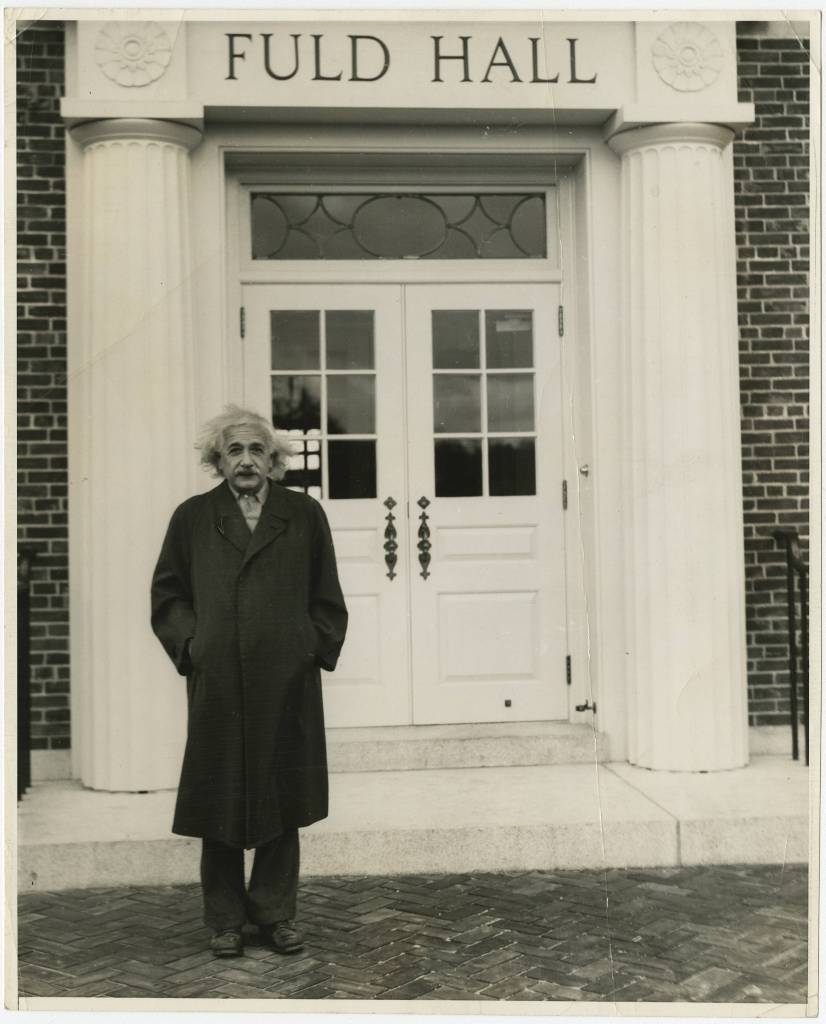

Above: The Institute’s first building was Fuld Hall. I’ve included a photograph of Einstein standing outside of Fuld Hall in 1939 (source) and several photographs that I took in December 2024. Below: Several other assorted photographs of the Institute.